This week, let’s have some fun exploring neuroscience in ancient history. In fact, we’re going to go back all the way to ancient Egypt. Because early civilizations did not have appropriate methods to study the human brain, many of their initial assumptions about how the human brain and body functioned were inaccurate…but what they did presume is very interesting and entertaining to learn!

When was the earliest reference to the “brain”? Do you want to take a guess? The brain’s earliest reference goes all the way back to the 17th century BC, when it was noted in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian medical text on surgical trauma. It’s an amazing papyrus that describes 48 cases of wounds, dislocations, and injuries associated with the military, likely trauma sustained from the battlefield. In this papyrus, the hieroglyph representing the brain is seen in Figure 1.

By the way, it’s well known that the brain was removed during the mummification process, because it was believed that the heart was the seat of the soul and intelligence. We now know that the brain is the seat of intelligence, although we still say that we “memorize by heart.”

Moving on to ancient Greece, studies of the brain were documented in the works of Alcmaeon of Croton, a Greek philosopher-scientist and medical writer. In fact, it was Alcmaeon who first suggested that the brain, not the heart, controlled bodily functions and that our senses derived from the brain. Amazingly, Alcmaeon theorized that the brain also served as the repository for memory and thought. This is in contrast to the theories of Aristotle, who taught that the heart was the seat of intelligence, while the brain worked simply to cool the blood.

As we travel to the Roman Empire, we learn that the Greek physician and philosopher Galen developed several novel theories about brain function. To do so, Galen actually dissected the brains of pigs, apes, oxen, and other animals. He proposed that specific spinal nerves controlled certain muscles, and idea way ahead of his time—it wasn’t until the works of Francois Magendie and Charles Bell in the 19th century that Galen’s hypotheses were surpassed.

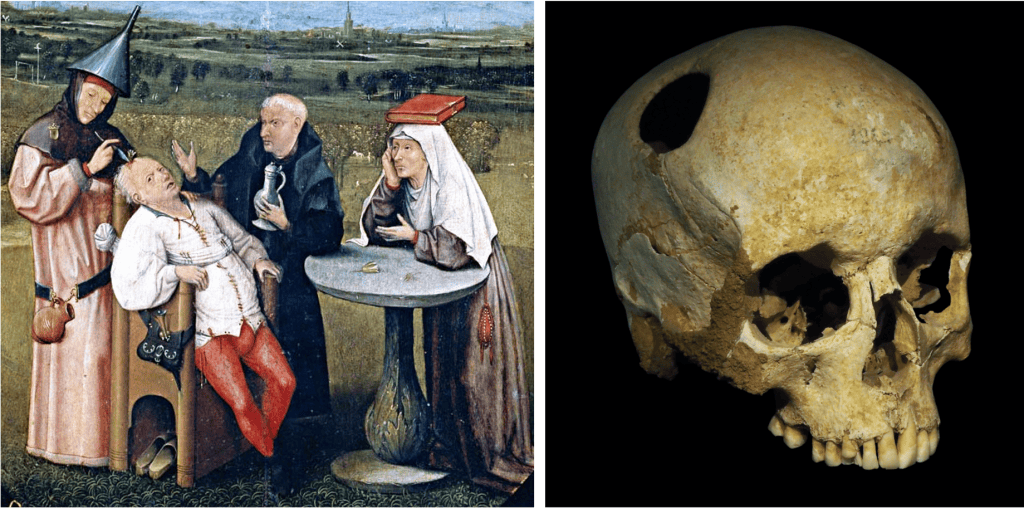

Finally, I can’t leave this article without talking about one of my favorite ancient brain surgery interventions, called trepanning (but also known as trepanation or making a burr hole). This is a procedure where a hole is drilled into the human skull while the patient is alive, all done during ancient times (I’m totally not kidding!). Trepanning creates a perforation into the cranium to expose the dura mater, which helps to relieve pressure from blood buildup following a skull injury (Figure 2). Besides injury, trepanning was done on a patient in ancient times when that person may have acted in an “abnormal” way, such as displaying psychiatric symptoms or seizures. Because psychiatric disease and epilepsy were thought to be caused by evil spirits inhabiting the body, trepanning was done to relieve those evil spirits from the head. How far back does trepanning go? There is evidence of trepanation as far back as prehistoric Neolithic times.